F O R M L A B

T H E A R T I S T E X P L O R E R

FormLaboratory: A Model for Geographically Dispersed Artist Exploration

Les Joynes, PhD

Founder, FormLaboratory

Visiting Scholar in Art and Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York

Visiting Faculty, School of Art, Renmin University, Beijing;

US Public Diplomacy/ Fulbright-Hays Award Mongolia (2014), China (2017)

As part of Going Beyond: Art as Adventure. Published by Cambridge Scholars, UK, 2017

This page is a supplement for The Artist Explorer: FormLaboratory: A Model for Geographically Dispersed Artist Exploration (2016). It includes images and links to videos related to the text. 1996-2017 © FormLAB. FormLaboratory, Les Joynes, ARS, New York. All Rights Reserved. This item is protected by original copyright and licensed under Creative Commons License and Artist Rights Society, New York and DACS, London. All images and text 1996-2016 © Les Joynes, Form-Laboratory, FormLAB and ARS, New York.

Click for here for 2 min video trailer.

Click on thumbnail below:

_______________

1996-2017 © FormLAB. FormLaboratory, Les Joynes, ARS, New York. All Rights Reserved. This item is protected by original copyright and licensed under Creative Commons License and Artist Rights Society, New York and DACS, London. All images and text 1996-2016 © Les Joynes, Form-Laboratory, FormLAB and ARS, New York.

[Abstract]

Today, the advancement of globalization, communication and cultural exchange have prompted artists to search for new and significant ways of making art in an effort to create communities and initiate intercultural dialogue that can help us better understand our societies and ourselves.

FormLaboratory (FormLAB) was conceived by American artist, Les Joynes in 1996 as a vehicle for geographical exploration. It serves as a space to observe the phenomena of in-situ art-making and the examination of notions of global and local cultural identity. The unfamiliarity of each site creates a uniquely reactive and relatively destabilized context for art-making and intercultural collaboration. Inspired by the archeological laboratory, FormLaboratory has created performances and exhibitions in the US, Germany, Singapore, France, Brazil, Korea and Mongolia. FormLaboratory is preparing to exhibit at the Inside Out Art Museum in Beijing, China in 2017.

At the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture (2012), Joynes and a Brazilian shaman created sculptures together from sacred and magical objects. In 2014, he led an expedition to the Mongolian-Siberian border to visit nomadic Tsaatan reindeer herders and participate in rituals and create performances inspired by indigenous shamanism. For a 2014 museum exhibition in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital, Joynes created a series of performances with Mongolian artists, traditional musicians and dancers as well as contemporary musicians as a way of exploring Interdisciplinarity.

This paper deconstructs the experiments carried out in Brazil (2012-2013) and in Mongolia (2014).

1996-2016 © FormLAB, Les Joynes, ARS, New York. All Rights Reserved.

Background: Exploring the unfamiliar

Why explore?

T.S. Elliot writes, “Exploration will be to arrive where we began and to know the place for the first time.” Exploration creates an opportunity for the artist to encounter the unfamiliar, to learn, and evolve.

Through a geographically-dispersed artist practice, I challenge myself in each new location through the adoption of new processes, materials, and unfamiliar traditions. Exploration and experimentation within unfamiliar contexts forces me to make my practice reactive, creating new combinations and approaches to art-making.

As a Southern California native, I began in the 1970s collecting and photographing found objects off beaches, forests, abandoned construction sites and flea markets. To me, they represented “living installations,” unintentional assemblages and arrangements of objects in neighborhoods, private gardens, two-car garages and constructions sites. With my camera, I captured slices of the small-town topographies that mirrored the community.

With a still-camera I discovered that I could freeze memory, immortalizing objects found-assemblages impromptu and in the moment. Impromptu assemblages possess a sense of historicity an almost tangible moment of being placed by human hands in a particular way, within a sense of ordering. These piles of stuff did not allude to art nor did their unwitting sculptors think they would be observed by another as art. This lack of implied aesthetic purpose gives these assemblages and objects a sense of the authentic simply in its being.

Living in London in the 1990s I started mudlarking (collecting on riverbeds at low tide). In the brown-gray silt and mud I wandered, and discovered an array of found objects including old bones, worn bricks, fragments of 19th century bottles and clay pipes, porcelain plate shards sometimes bearing ship logos, and the occasional doll appendage. Anything jettisoned into the Thames from pipes, over the edge of embankments, or from sides of ships, became submerged in the river bed.

At Goldsmiths College, London, I explored the notion of the studio-as-laboratory. I moved the studio beyond four walls to become a mobile structure of preservation to collect, observe, arrange and display these found objects to the world. Beginning in 2002, I expanded the scope of the lab to not only delve more deeply into the essence of found objects, but also to explore unfamiliar geographic contexts. During the next 15 years, I evolved this into a studio/laboratory that would move with me to new sites and become an important interface in which I could learn more about other cultures.

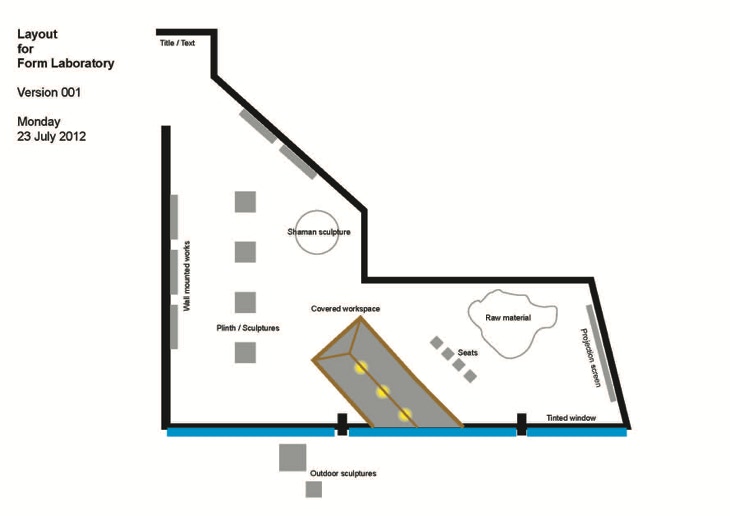

In the next section I introduce the developmental concept of FormLaboratory, how it grew into a system to observe art processes in the studio and later into a nomadic structure to observe the unfamiliar in different cultural contexts and through shared processes with other individuals. (See image 2)

Eliot, T. S. (1942) Little Gidding, London, Faber and Faber.

“…photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of a space in which they are insecure.” Susan Sontag (1977) On Photography, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p.9.

Philip K Dick in his novel The Man in the High Castle which describes an object as one that inherently possesses a memory of history or event: “He gives her two very similar-looking cigarette lighters, one of which is worth 'maybe forty or fifty thousand dollars on the collector's market.' Why? Because of 'the historicity’. She said, 'what is "historicity”?’ When a thing has history in it. Listen. One of those two Zippo lighters was in Franklin D. Roosevelt's pocket when he was assassinated. And one wasn't. One has historicity, a hell of a lot of it. As much as any object ever had.“ (Dick, P.K. 1962 pp. 65-66)

By “authentic” I am referring to a found-object being discarded, abject, essentially submerged into the chaos of the landscape, or possibly buried or lost at the back of a second-hand shop. The object lacks the currency one may place on an objet d’art. It is and thus without value. It is for me – just as it is – authentic in its abjectness. From Greek authentikos 'principal, genuine', Oxford English Dictionary. [Internet].

(http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/authentic). Retrieved January 4, 2016.

In the early 2000s curators began to express an interest in the notion of the laboratory as ‘still untouched by science’ from “Laboratories is the answer, what is the question?” TRANS 8 (2000) from Bishop, Clare, (2004) Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics: October (Fall 2004): pp. 51-79.

As FormLaboratory developed (Berlin, 2008; Singapore, 2009; New York, 2009; Treignac, France, 2010; and Seoul, 2012), I began to entreat disruption and the unfamiliar within my art-making processes particularly within unfamiliar environments.

On www.formlaboratory.com/artistexplorer.html I include videos and images of FormLaboratory’s second iteration (FormLAB, Treignac, 2010) at an art center located on the grounds of a former 19th century textile factory. This iteration shows the emergence of shared practice between two artists constructing assemblages from found objects collected in surrounding locales.

Unfamiliar contexts: Producing FormLaboratory, I worked with a variety of artists and local inhabitants in different geographic settings. I drew inspiration from French Surrealist André Breton’s (1989-1966) Cadavre Exquis games and how these game presented the opportunity to destabilize art-making processes.

By presenting “live” art or art-making as a process (observable within performance spaces such as a museum), I sought to interrupt the spectators’ passive gaze. I presented them with spontaneity and movement encouraging them to experience works of art as a dynamic series of processes with multiple outcomes that continually change over the duration of the exhibition. (8) The radical nature of shared art-making can lead to unexpected discoveries that are unique to local-specific contexts, bringing about new ways of engaging with art, sites and performances. This has the potential to disrupt the static visual economies and narratives often reinforced by museums, art fairs and commercial galleries. (9)

Shared processes with others and utilizing found objects that have been collected over time offers a structure where I can explore the spaces between the Self and the Other. (10) FormLaboratory becomes a lens into cultural traditions through the creation of dynamic interdisciplinary structures (what I refer to as shared art-making). It appropriates found-objects, sound, music, oral tradition, performance, and emergent technologies and reinterprets them anew. Shared processes with local inhabitants of an unfamiliar culture creates an othering of self and a resulting parapraxis (11) through the invocation of a subconscious. Michel Foucault writes of an “…unveiling of the non-conscious.” It is this “othering of the self” (13) that evokes a fecund unfamiliar territory in my practice.

In Brazil (2012, 2013) and Mongolia (2014) I explored these disruptions through interdisciplinary collaboration, not only working with other artists but also working with individuals and groups outside of the discipline of visual arts, which led me to develop projects with a shaman and traditional and contemporary musicians.

In the next section, I introduce two recent interactions of FormLaboratory in Brazil and Mongolia.

(8) For me observers include the artists, participants and the spectators. The LAB disrupts expectations of the processes (which engage the unfamiliar) and destabilizes the notion of the exhibition being a passive display of works of art: sculpture, drawings, installations, moving image, photographs – the collections of which may change and mutate during the exhibition.

(9) Robert Smithson in his essay “Cultural Confinement” (1972) writes: “A work of art when placed in a gallery loses its charge and becomes a transient object or surface disengaged with the outside world. A vacant white room with lights is still a submission to the neutral. Works of art seen in such spaces seem to be going through a kind of aesthetic convalescence. They are looked upon as so many inanimate invalids, waiting for critics to pronounce them curable or incurable. Next comes integration. “Once the work of art is totally neutralized, ineffective, abstracted, safe, and politically lobotomized, it is ready to be consumed by society. All is reduced to visual fodder and transportable merchandise. Innovations are allowed only if they support this kind of confinement” (Smithson, 1996, pp. 154-155).

(10) Okwui Enwezor writes of the receiver of the artwork encountering “a phenomenological space within which dimensions of temporal and historical, aesthetic and critical methodological and disciplinary models converge so as to produce new relationships of proximity. Enwezor, O. and Bouteloup, M.[et al.] (2012) Intense Proximity: an Anthology of the Near and the Far, Paris: Artlys, Centre National des Arts Plastiques, p 11.

(11) “an error in speech, memory, or physical action that is interpreted as occurring due to the interference of an unconscious ("dynamically repressed") subdued wish, conflict, or train of thought guided by the ego and the rules of correct behavior” Wikipedia [Internet] Accessed January 21 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freudian_slip

(12) Foucault, M. (1970) The Order of Things: Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York, Vintage Books. P 364.

(13) There is a sense of the self being “buttressed” through self opposition a notion that we are that we are that what we are not in Hal, F (1996) in The Artist as Ethnographer in The Return of the Real, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 179-180.

Site and magic: FormLAB-São Paulo (2012)

Brazilian Museum of Sculpture, São Paulo, Brazil

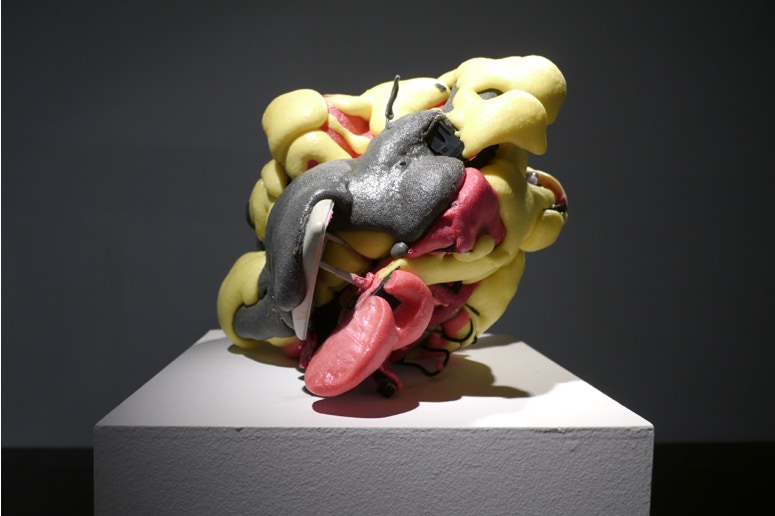

FormLAB at the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture in 2012. The outcomes of this exhibition included a multi-media installation in the museum: a lab structure and assemblages created within the lab, videos of found object collection and live performances during the exhibition. (see images 4, 5, 6)

Working with a shaman in Brazil became turning point for Form Laboratory because it introduced shared processes with individuals outside of the arts. I was also curious to learn about a magical world, the Pai-de-Santo, a Candomblé priest, perceived in rituals and within objects. We both mutually benefited from this experience. He wished to explore art-making as part of his Candomblé practice and I sought learn about Brazilian culture through its multi-faceted mystical ceremonies.

The output included single and two-channel video documentation, individual and group performances, an installation (see images 2 and 9) as well as discrete sculptures including a hanging sculpture. These outputs became a documentation of the events of the artists-interface with the culture.

FormLaboratory in São Paulo was an opportunity for me to further visualize the laboratory space as studio, stage and in a sense, panopticon, in which I could experiment and risk failure while my spectators could observe creative cooperation and the emergence of the artifact.

For several weeks prior and during the exhibition I collected objects from various neighborhoods around São Paulo in Centro, Cidade do Paraíso, Vila Mariana, Jardins, Praça da Luz. Higienópolis, Jardins, Avenida Paulista, Liberdade, Pinheiros, Praça da Praça da Sé and Anhangabaú. I also worked with local university students who collected found objects from different areas of the city toting the objects each day to the museum where I combined them into found object assemblages utilizing twine and plastic foam. (see still image of outdoor performance using plastic foam, and found objects at the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture, São Paulo, July 2012. See image 7)

The Laboratory became a lens and a catalyst for me to explore São Paulo through its topographies, found objects, sites and cultural traditions, exploring what American artist Gordon Matta-Clark -1943-1978) referred to as a city’s ‘living archeology.’

In Brazil I discovered how FormLaboratory simultaneously inhabited both private and public spaces. It became a structure in which I could build unique and unpredictable personal connections with these sites and inhabitants. Symbolically it became a vehicle for my nomadic practice fostering the creation of my own personal micro-heterotopias.

In São Paulo, I conceptualized the exhibition space as a processing site and observation center, creating a central Laboratory structure and a space displaying both raw material, works in process and completed assemblages. As the exhibition progressed, the museum space was populated by sculptures that were created daily during the exhibition in and around the museum. (see images 8 and 9)

At the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture I created performances that combine the lab’s process-based making structure with the practice of local ritual. These were captured in a series of two-channel HD videos that were presented during the exhibition. The exhibition changed daily. As new performances were created they and the artifacts were added to the exhibition so that the museum visitor could experience a sense of observe multiple timelines and recursivity. Museum visitors could come the next day and experience different events, videos and objects.

The artifact created during the performance was installed near the exhibition’s entrance.

(see image 15).

By bringing FormLaboratory to Brazil I wanted to use art making processes as a way to explore its numerous and often hidden layers of culture. During the three months I was there in 2012 I discovered unfamiliar yet fecund niches of culture particularly through Brazil’s unique indigenous rituals through which I began to comprehend how others may so differently perceive form and space. (18)

Through its daily documentation I was also aware that I was making certain decisions how I documented these events. Should events be documented through the open mechanical eye of the camera “passively recording reality” while roving between what occurs, what is framed, and what is desired by the operator? (19) How would the camera record the view from the perspective of the artist (or collector) and that of the artist? Jean Rouch speaks of the filmmaker’s use of the camera as participant in a cinema verité, (20) something that reveals a mechanical eye’s gaze on a specific event. (21) Is this event truthful, or is the mere presence of the camera undermining its aim of objectivity? (22)

Can it be ethnologically objective? Or does it need to be? And if so, how would I achieve this? It also poses an important question around how the artist questions himself or herself within different geo-cultural contexts.

18. Michael Taussig writes, “Underlying all our mystic states are corporeal techniques, biological methods of entering into communication with God. According to Marcel Mauss, “Les Techniques du Corps,” Lecture 17, May, 1934, translated by Ben Brewster as “Body Techniques,” in Marcel Mauss, Sociology and Psychology (1979), London: Routledge. Pp. 95–123.

19 Malcolm Turvey in his article “Vertov, the View from Nowhere,” and the expanding “Circle,” (October 148, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014, p 81).

20 Ethnographer, Jean Rouch (1917-2004) writes about the invention of the cinematic eye stating, “Dziga Vertov understood that cinematic vision was a particular kind of seeing, using a new organ of perception – the camera. This new perception had little in common with the human eye; he called it the ‘ciné-eye.’ Rouch, Jean in Intense Proximity: an Anthology of the Near and the Far (2012), on “The Vicissitudes of the Self: the Possessed Dancer, the Magician, the Sorcerer, the Filmmaker, and the Ethnographer,” (Paris, Artlys, Centre national des arts plastiques, p 368).

21 Susan Sontag writes in On Photography, “…photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of a space in which they are insecure,” (New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p.9).

22 In Boutang and Chevallay’s documentary film, Lévi-Strauss in His Own Words, Claude Levi-Strauss refers to Tristes Tropiques as written “with a lens that’s called a fish eye...It shows not only what is in front of the camera, but also what is behind the camera. And so, it is not an objective view of my ethnological experiences, it’s a look at myself living these experiences.” (1955) Levi-Strauss in Boutang, PA and Chevallay A. Claude (2008), Lévi-Strauss in His Own Words (Claude Levi-Strauss par lui-meme), (Arte Editions, [documentary film], Time code 1:04:50).